- Home

- Rohit Bhargava

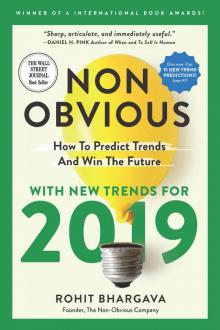

Non-Obvious 2019- How To Predict Trends and Win The Future Page 4

Non-Obvious 2019- How To Predict Trends and Win The Future Read online

Page 4

How to Be Fickle

Resist the urge to fully understand or analyze ideas in the moment you save them.

People often cast the idea of being fickle as a bad thing. When we hear the word, we tend to think of all the negative situations where we abandon people or ideas too quickly, but there is an upside to learning how to be purposefully fickle.

On the surface, this may seem counterintuitive. After all, why wouldn’t you take the time to analyze a great idea and develop a point of view? There are certainly many situations when you do this already.

But you probably never do the opposite. A key element of becoming an idea curator is saving ideas for later digestion. As you will see in Chapter 3, where I share my specific methods for curating trends, this idea of saving an idea so I can return to it later when it may have more value is a very fundamental part of the method I use for trend curation.

Often the connection between ideas will only come from the discipline of setting them aside and choosing to analyze them later, when you have more stories and added perspective to see the connections. Being fickle isn’t about avoiding thought—it’s about freeing yourself from the pressure to recognize connections immediately and making it easier to come back to an idea later for analysis.

3 Ways to Be More Fickle

Save Ideas Offline. There are countless digital productivity tools, such as Evernote, but they can be hard to manage and navigate when you need them. Instead, I routinely print articles, rip stories out of magazines, and put them all into a single trend folder that sits on my desk. Saving ideas offline allows me to physically spread them out later to analyze more easily.

Use a Timer. To avoid the temptation to overanalyze an idea in the moment, set a timer as a reminder to go back. It will help you to clear your mind in the interim. The other benefit of using a timer is that it can force you to evaluate things more quickly and just focus on the big picture.

Take Notes with a Sharpie. I mark the many articles and stories I find throughout the year with a few words to remind me of the theme of the article and story. I use a Sharpie marker because the thicker lettering stands out and encourages me subtly to write less. This same trick can help you to make only the most useful observations in the moment and save any others for later.

Be Fickle: What to Read

The Laws of Simplicity, by John Maeda. Maeda is a master of design and technology, and his advice has guided many companies and entrepreneurs toward building more amazing products. In this short book, he shares some essential advice for learning to see the world like a designer and how to reduce the noise in order to see and think more clearly.

How to Make Sense of Any Mess, by Abby Covert. I have read many books on the art of organizing information, but this one, with its smart reasoning and simplified approach, is one of my favorites. The author is an Information Architect who goes by the pseudonym “Abby the IA” and shares methods based on more than ten years of teaching experience that are worth adopting and sharing with your entire team.

How to Be Thoughtful

Take the time to reflect on a point of view before sharing it in a considered way.

In 2014, after ten years of writing my business and marketing blog, I decided to stop allowing comments. For some readers, this seemed counter to one of the fundamental principles of blogging, which is to create a dialogue.

The reason I stopped was simple. I had noticed a steady decline in the quality of comments. What was once a robust discussion involving thoughtfully worded responses had devolved into a combination of thumbs-up–style comments and spam.

Thanks to anonymous commenting and the ease of sharing knee-jerk responses, comments had lost their thoughtfulness—and people were starting to notice. Thus, I turned off the comments.

The web is filled with this type of “conversation.” Angry, biased, half-thought-out responses to articles, people, or media. Being thoughtful is harder to do when the priority is to share a response in real time. Yet the people who are routinely thoughtful are the ones who gain and keep respect. They add value instead of noise... and you can be one of them.

3 Ways to Be More Thoughtful

Wait a Moment. The beauty and challenge of the Internet is that it occurs in real time. It’s easy to think that if you can’t be the first person to comment on something, your thoughts are too late. That’s rarely true. “Real time” shouldn’t mean sharing a comment from the top of your head within seconds. Take your time before writing a comment or sharing a link and consider what you’re about to say—and whether you’d still be proud to say it twenty-four hours from now.

Write and then Rewrite. When it comes to being thoughtful with writing, all of the most talented writers take time to rewrite their thinking instead of sharing the first thing that they write down. The process of rewriting can seem like a big-time commitment, but the fastest form of writing is dialogue—so when in doubt, write it like you would say it.

Embrace the Pauses. As a speaker, becoming comfortable with silence took me years to master. It’s not an easy thing to do. Yet when you can use pauses effectively, you can emphasize the things you really want people to hear and give yourself time to craft the perfect thing to say.

Be Thoughtful: What to Read

Brain Pickings, by Maria Popova. Popova describes herself as an “interestingness hunter-gatherer,” and she has one of the most popular independently run blogs in the world. Every week she publishes articles combining lessons from literature, art, and history on wide-ranging topics like creative leadership and the gift of friendship. The way she presents her thoughts is a perfect aspirational example of how to publish something thoughtful week after week.

How to Be Elegant

Describe concepts in more beautiful, deliberate, and simple ways.

Jeff Karp is a scientist inspired by elegance . . . and jellyfish.

As an associate professor at Harvard Medical School, Karp’s research focuses on using bio-inspiration—inspiration from nature—to develop new solutions for all types of medical challenges. His self-named Karp Lab has developed innovations such as a device inspired by jellyfish tentacles to capture circulating tumor cells in cancer patients and better surgical staples inspired by porcupine quills.

Nature is filled with elegant solutions, from the way that forest fires spread the seeds of certain plants to the way termites build porous structures with built-in heating and cooling.

I believe it’s this idea of simplicity that’s fundamental to developing elegant ideas. As Albert Einstein famously said, “make things as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

A good example of things described beautifully is in what talented poets do. Great poetry has simplicity, emotion, and beauty because superfluous words are edited out of the verse. Poets are masters of elegance; they obsess over language and understand that less can mean more.

You don’t need to become a poet overnight, but some of these principles can help you get better at creating more elegant descriptions of your own ideas. To illustrate how, here’s the process I used to name my trends in previous reports.

3 Ways to Think More Elegantly

Start with the Obvious. One of the most popular trends from my 2015 Non-Obvious Trend Report was something I called “Selfie Confidence.” The name was a play on “self-confidence” and was written to force people to see something they were already familiar with in a new way. Selfies are often criticized as demonstrations of narcissism, but the trend also suggested the idea that selfies might contribute to helping people to grow their self-esteem.

Keep It Short. One thing you’ll notice if you look back on any of the previous years’ trends (including this year) is that the title for most trends are no longer than two words. Elegance often goes hand in hand with simplicity, and this usually means using as few words as possible.

Use Poetic Principles. Poets use metaphors and imagery instead of obvious language. In Chapter 3 you’ll get an inside look at how I use techniques borrowed fr

om poetry as part of the naming process I use every year for trends. A quick scan of past trends will also illustrate how I’ve used these principles to describe trends like “Preserved Past” or “Lovable Unperfection.”

Be Elegant: What to Read

Einstein’s Dreams, by Alan Lightman. This book, written by an MIT physicist and one of my favorites, creatively imagines what Einstein’s dreams must have been like and explores them in a beautiful way through short chapters with interesting assumptions about time and space. This is not a book of poetry, but it’ll introduce you to the power of poetic writing while also offering the most elegant description of the nature of time that you’ll ever read.

Any Book by Dr. Seuss. This may seem like an odd suggestion, but Dr. Seuss had a great talent for sharing big ideas with simplicity and elegance. You probably already know some of his brilliance: “Today you are you, that is truer than true. There is no one alive who is youer than you.” Reading his work, though, will remind you of the power of finding just the right words while inspiring you to do more with less.

Why These 5 Habits?

Do these five habits for helping you to learn the art of curating ideas seem a bit surprising? The fact is, the process of how I came to these five involved an exercise of curation in itself.

Over the past several years, I read interviews with professional art curators and how they learned their craft. I bought more than a dozen books written by trend forecasters, futurists, and innovators. I interviewed dozens of top business leaders and authors. I carefully studied my own behavior. I tested the effectiveness and resonance of these habits by teaching them to my students at Georgetown University and professionals in private workshops.

Ultimately, I selected the five habits presented here because they were the most helpful, descriptive, easy to learn, and effective once you learn to put them into action.

As a recap before we get started with a step-by-step approach to curating trends, let’s do a review:

03

The Haystack Method:

How to Curate Trends for

Fun and Profit

“The most reliable way to anticipate the future

is to understand the present.”

JOHN NAISBITT, Futurist and Author of Megatrends

_

In 1982, a book called Megatrends changed the way governments, businesses, and people thought about the future.

Author John Naisbitt was one of the first to predict our evolution from an industrial society to an information society, and he did so more than a decade before the advent of the Internet. He also predicted the shift from hierarchies to networks and the rise of the global economy.

Despite the book’s unapologetic American-style optimism, most of the ten major shifts described in Megatrends were so far ahead of their time that when it was first released one reviewer glowingly described it as “the next best thing to a crystal ball.” With more than 14 million copies sold worldwide, it’s still the single bestselling book about the future published in the last forty years.

For his part, Naisbitt believed deeply in the power of observation to understand the present before trying to predict the future (as the opening quote to this chapter illustrates). In interviews, friends and family often described Naisbitt as having a “boundless curiosity about people, cultures and organizations,” even noting that he had a habit of scanning “hundreds of newspapers and magazines, from Scientific American to Tricycle, a Buddhism magazine” in search of new ideas.[9]

John Naisbitt was and still is (at a spry eighty-eight!) a collector of ideas. For years, his ideology has inspired me to think about the world with a similarly broad lens and has helped me to develop the process I use for my own trend work, which I call the Haystack Method.

Inside the Haystack Method

It’s tempting to describe the art of finding trends with the cliché of finding a “needle in a haystack.” This common visual reference brings to mind the myth of trend spotting that I discounted in Chapter 1. Uncovering trends hardly ever involves them sitting in plain sight waiting for us to spot them.

The Haystack Method describes a process where you first focus on gathering stories and ideas (the hay) and then use them to define a trend (the needle), which gives meaning to them all collectively.

In this method, the work comes from assembling the information and curating it into groupings that make sense. The needle is the insight you apply to this collection of information to describe what it means—and to curate information and stories into a definable trend.

While that describes the method with metaphors, to learn how to do it for yourself we need to go deeper. Starting with the story of why I created the Haystack Method in the first place.

Why I Started Curating Ideas

The Haystick Method was born out of frustration.

In 2004, I was part of a team that was starting one of the first social media–focused practices within a large marketing agency. The idea was that we would help big companies figure out how to use this new platform as a part of their marketing efforts.

The aim of our team was to help brands work with influential bloggers, because in 2004 (prior to Facebook and Twitter) “social media” mainly referred to blogging. There was only one problem with this well-intentioned plan—none of us knew very much about blogging.

So we did the only thing that seemed logical to do: each of us started blogging.

In June of that year I started my “Influential Marketing Blog” with an aim to write about marketing, public relations, and advertising strategy. My first post was on the dull topic of optimal screen size for web designers. Within a few days I ran into my first challenge: I had no plan for what to write about next.

How was I going to keep this hastily created blog current with new ideas and stories when I already had a full-time day job that wasn’t meant to involve spending time writing a blog? I realized I had to become more disciplined about how I collected ideas.

At first I focused on finding ideas for blog posts, usually collected by scribbling them into a notebook or emailing them to myself. Then I decided to include ideas from the daily brainstorming meetings I attended. Pretty soon I expanded to saving quotes from books and ripping pages out of magazines.

Those first four years of blogging helped me land my first book deal with McGraw-Hill. Several years later, in 2011, the desire to write a blog post about trends based on ideas I had collected across the year led me to publish the first edition of my Non-Obvious Trend Report.[10]

My point in sharing this story is to illustrate how the pressure to find enough ideas worth writing about consistently on my blog helped me to get better at saving and sharing ideas that people cared about. Blogging helped me become a collector of ideas, which is the perfect introduction to the first step in the Haystack Method.

Step 1—Gathering

Gathering is the disciplined act of collecting stories and ideas from reading, listening and speaking to different sources.

Photo: Sources used for gathering information.

Do you read the same sources of media religiously every day? Or do you skim social media occasionally and sometimes click on the links your connections share to continue reading? Regardless of your media diet, chances are you encounter plenty of interesting stories or ideas. The real question is: Do you have a useful method for saving them? The key to gathering ideas is making a habit of saving interesting things in a way that allows you to find and explore them later.

My method involves always carrying a small passport-sized notebook in my pocket and keeping a folder on my desk to save media clippings and printouts. By the time you read these words, that folder on my desk has changed color and probably already says “2019 Trends” on the outside of it. In my process, I start the clock every January and complete it each December for my annual Non-Obvious Trend Report (see Part II of this book). Thanks to this deliverable, I have a clear starting and ending point for each new round of ideas that I collect.

/>

You don’t need to follow as rigid a calendar timetable as I do, but it is valuable to set a specific time for yourself to review and reflect on what you have gathered in order to uncover the bigger insights (a point we will explore in subsequent steps).

Idea Sources:

Where to Gather Ideas

Personal conversations at events or meetings

Listening to live speakers or TED Talks

Entertainment

Books

Museums

Magazines and newspapers

Travel!

This list of sources might seem, well, obvious. It’s rarely the sources of information themselves that will lead you toward a perfectly packaged idea or trend. Rather, mastering the art of gathering valuable ideas means training yourself to uncover interesting ideas across multiple sources, and becoming diligent about collecting them. One thing that will help is learning to take better notes. See the chart on the following page for some tips on how to do it.

Tips & Tricks: How to Gather Ideas

Start a Folder. A folder on my desk stores handwritten ideas I find interesting, articles ripped out of magazines and newspapers, printouts of articles from the Internet, brochures from conferences, and the occasional odd object (like a giveaway from a conference or a brochure received in the mail). This folder lets me store things in a central and highly visible way. You might choose to create this folder digitally or with paper. Either way, the important thing is to have a centralized place where you can save ideas for later digestion.

Non-Obvious 2019- How To Predict Trends and Win The Future

Non-Obvious 2019- How To Predict Trends and Win The Future